Gouda Pipe Fragments

- Museum Kota Lama

- Oct 10, 2023

- 6 min read

Updated: Oct 15, 2023

Dating: 1600s - 1900s (16th - 18th centuries AD)

This Gouda pipe fragment is the result of an excavation conducted by the Yogyakarta Archaeological Centre in 2011-2012 at the locus of Kota Lama Semarang. Based on the identification that has been done, the fragments consist of 6 (six) different individuals and consist of 1 (one) part of the Tobacco Chamber commonly referred to as "Stummel", and 5 (five) parts of the pipe stem.

The Tobacco Bowl / Stummel fragment has a length of 4.2 cm, with the outermost and widest diameter of 2.5 cm, and the diameter of the part close to the pipe stem is approximately 1.5 cm. Meanwhile, the stem fragments vary in length between 2.5 cm for the smallest individual and 4.6 cm for the longest individual. Regarding the diameter of the five stem fragments, four of the fragments have the same diameter of 0.6 cm, while one of the stem fragments with the thickest dimensions has a diameter of 0.8 cm.

Gouda pipe is one of the tools used to consume tobacco by burning or smoking, long before cigarettes were produced and started to be mass-marketed (around the end of the 19th century). The name Gouda refers to one of the names of a clay pipe-producing town in the Netherlands that was famous for its quality in the 17th - 18th centuries. However, the existence of Gouda pipes in the Netherlands is inseparable from the role of English missionaries and mercenaries/soldiers of fortune who brought the influence and knowledge of clay pipe-making to the Netherlands in the early 1600s (17th century).

By 1610, the first tobacco pipe manufacturers in the Netherlands were slowly emerging in the Amsterdam and Leiden areas, albeit as small family enterprises. A few decades later, the clay pipe industry grew and spread to Gouda, Enkhuizen, Rotterdam, Delft, and Schoonhoven. By the mid-1640s, more and more regions had joined the clay pipe industry, including Zwolle, Deventer and Middelburg, Gronigen, and Maastricht. But of all the clay pipe-producing towns, Gouda's name is the only one that is recognised.

Dating :

In terms of the dating of the object, based on a comparison of the typology of clay pipes produced in the Netherlands, it is likely that the Gouda pipe fragment on display was made in the range of 1680-1710 or 1700-1710 (see figure below for the typology and style of Gouda pipes from 1600-1820). However, the year number predicted is a relative year number that arises from comparing the general shape of the stummel parts. This is due to the incomplete condition of the object, as well as the loss of the Heel-marks or stamps commonly found at the bottom of the stummel, which generally indicate where the pipe was and by what firm it was produced.

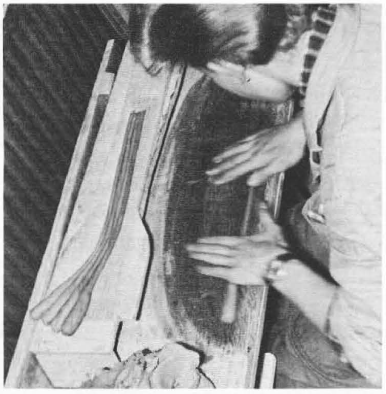

Based on a cursory observation, the stummel fragment displayed in the museum is thought to have a similar shape to the fragment in the picture. It can be seen from the angle of intersection between the stummel parts with the same stem and the lower part which tends to be convex while the upper part of the stummel has the same angle. So it is estimated that the Gouda fragments in the museum collection used the same mold and were most likely produced in the same location. However, it is necessary to conduct further in-depth studies and comparisons with other clay pipe fragment samples to hypothesise the number of years, and where the pipe might have been produced.

Clay pipe/Gouda pipe manufacturing technology and process:

Regarding its manufacture, Gouda pipes or clay pipes are mostly produced by hand-made process and use white clay that has been baked as the basic material. The very first process to go through is the separation of contamination of other materials present in the white clay; this process is called zoken, from this process then produces muis or white clay material which will then be adjusted as needed.

In the next step, the pipe-maker will place the muis on a rollenbank/roller bench or a cutting board to roll the muis until it forms a lump at the end (bosjes rollen), with the size adjusted to the size of the pipe mold that will be used.

Before proceeding to the drying process, the pipe maker will usually make a hole that connects the stummel with the stem to the mouthpiece of the pipe which is commonly called the smoking channel. This process uses a tool called a weijer (a kind of iron needle or pin that is generally equipped with a handle). The process of making a hole or smoking channel is not by poking the weijer into the clay, but rather the clay is pushed over the weijer that has been greased beforehand until it forms a connecting hole.

After the connecting holes are formed, the pre-shaped clay pipe is put into a pipe mold (this mold is called a bipartite vorm or pipe mold; it is generally a two-sided mold and is made of bronze) that has been greased with lubricant or oil. The mold containing the soil pipe is then closed and placed on a bench vice to be pressed until the clay pipe inside has the shape of the mold. The next step is to re-punch the stummel using a conical metal ("stopper") that has been lubricated, by pushing it repeatedly against the non-moulded pipe to form the Tobacco bowl. The end of this stage is to remove any residual clay from the pressing mold process and form the tobacco bowl.

The process continues when the pipe mold is opened, and the formed clay pipe is lifted slowly and carefully, especially when lifting the tobacco bowl. The weijer is also gently removed, before adding the pipe maker's trademark or initials to the bottom of the tobacco bowl. The pipe is then dried for between 3 days to up to 1 week.

After the drying process is complete. The pipes will be put into the oven and baked at a maximum temperature of 1050˚C, and when the baking process is complete it is common to glaze or paint if needed, and if glaze and ornamentation are applied, then the baking process will be done again.

Use of Clay Pipe/Gouda Pipe in Java:

The use of tobacco pipes in Java reached its culmination in the 17th-18th centuries (late 1600s to 1760s), when both ceramic and wooden pipes were widely used by people in Java (not only by Europeans, and Javanese aristocrats). Alongside the heyday of the tobacco pipe, from as early as 1658, when local cigarettes began to appear (known as "bungkus" or "klobot" consisting of Javanese tobacco wrapped in banana leaves or dried corn leaves), the use of pipes decreased in the 18th century.

Anthony Reid (1985) in the Kartasura Chronicle, states that tobacco was first introduced to the people of Central Java in the year Saka 1523 or in the AD dating system in the range of 1601-1602, and was introduced by burning (smoking) using a long pipe like fashionable Europeans. Van Goens (1956: 257) describes how Amangkurat I (1646-1677) of Mataram, when leaving the palace, would usually be accompanied by 30 young women; one of these women would bring his pipe and tobacco, another would bring a lighter to light and burn the tobacco in the pipe, and another would bring the king's betel set.

As porcelain pipes and wooden pipes began to be abandoned, the emergence of tobacco products in the form of cigarettes (packets, or in Java better known as klobot) in the 18th century indirectly contributed to the decreasing trend of smoking using pipes. At the end of the 19th century AD, the incessant pace of modernity, which even reached the level of lifestyle, led to the consumption of imported cigarettes and cigars, resulting in klobot being considered old-fashioned or the same as betel/ kinang.

The year 1924 was the first year that local cigarette factories appeared with international tobacco blend style products better known as "white cigarettes" produced by British American Tobacco (B.A.T) with a factory in Cirebon, and not long afterward a B.A.T factory was also established in Semarang.

The existence of the Gouda Pipe signifies the tobacco consumption activities brought by Europeans in Java, more specifically Semarang; and indirectly shows the significance of Semarang's position as a port city and an important transit area in the distribution of tobacco commodities in Vorstenlanden for further export to Europe during the VOC occupation (1600-1799) and the Dutch Colonial period (1800-1940).

Comments